Last month the National Weather Service reported a bizarre cloud formation (left) moving erratically over southern Illinois. The “biological targets,” as the NWS called them, turned out to be a huge swarm of monarch butterflies migrating south. Despite risks related to drought and dwindling milkweed, they were headed to Mexico. If you’re an insect who weighs less than a postage stamp, how do you even consider a trip across the border? What if your brain is no bigger than the tip of a pencil, then what?

Last month the National Weather Service reported a bizarre cloud formation (left) moving erratically over southern Illinois. The “biological targets,” as the NWS called them, turned out to be a huge swarm of monarch butterflies migrating south. Despite risks related to drought and dwindling milkweed, they were headed to Mexico. If you’re an insect who weighs less than a postage stamp, how do you even consider a trip across the border? What if your brain is no bigger than the tip of a pencil, then what?

Laysan albatross are giants compared to monarchs. Still, you would be hard pressed to get a radar image of them unless they’ve gathered to feed at a mass squid spawn or the smorgasbord surrounding a factory fishing ship. “Colony” refers to their time spent on the ground during nesting season, or about 5% of their lives. The remaining 95% is spent wandering the open Pacific, and most of that is solo.

In order to attempt a map of meandering albatross, you have to to have all the right permits. You and your biologist colleagues have to get access to a colony where the birds are raising chicks. You have to hang out until a few parents come home, then capture them briefly. Then you have to wait for the data to tell you where the birds have traveled.

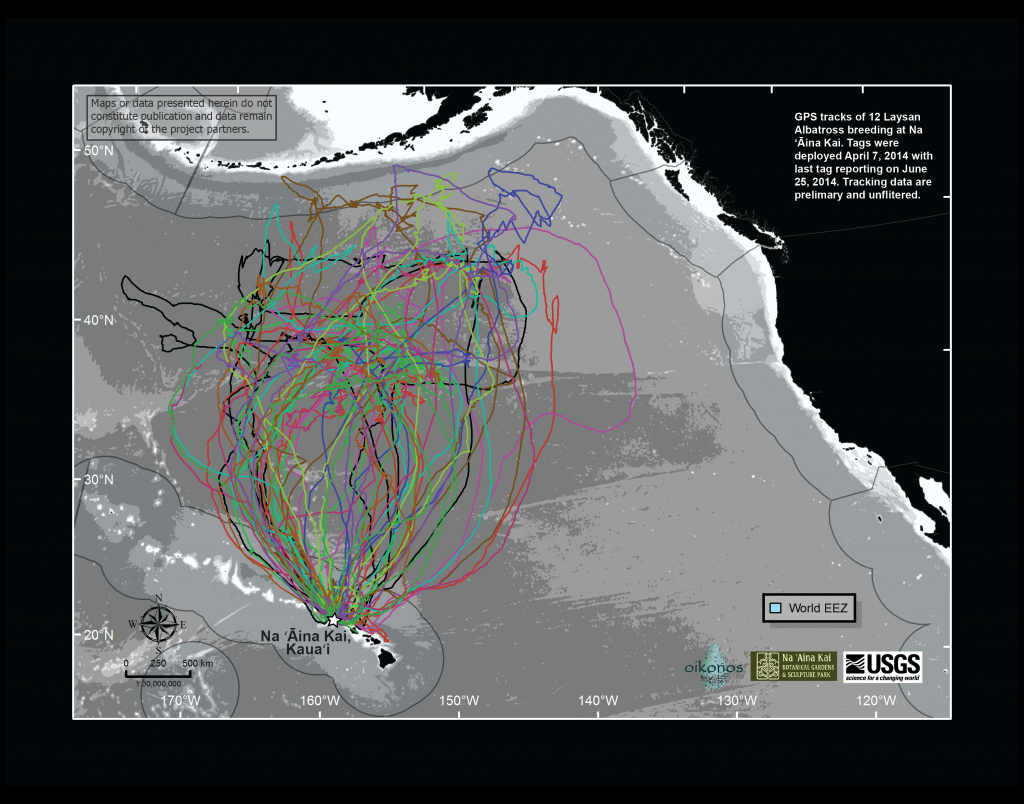

The good folks from Oikonos Ecosystem Knowledge, Pacific Rim Conservation and the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) accomplished all these tasks this year. A dozen birds got a lightweight GPS tag temporarily taped to feathers on their backs. The scientists then tracked them over a time span of 79 days. They assigned each bird a color and superimposed their flights on a map of the Pacific Ocean (above.)

If you show that map to your friends, you might discover you have a Rorschach on your hands. One person sees cotton candy, sweet and full of promise. Another person sees a frightening pattern of ocean depletion and pelagic plastic. Yet another person gets a good chuckle from the black line, saying it looks like a sketch of the state of Nebraska with a finger pointing northeast. She suggests we investigate the meaning of the finger. One person sees the Earth exhaling, another sees a fire.

Chris Jordan’s Billowing Streamers

For now let’s focus on the image perceived by the brilliant Seattle photographer, artist and filmmaker Chris Jordan. Chris, himself an albatross devotee, takes one look at the map and sees an image of colorful streamers billowing in the wind. He also notices how the birds’ origin and destination are always the same. “What’s most mind-blowing is not the fact that they can fly such long distances (which is incredible in itself) but the way they find their way home again,” he says.

Like swifts diving down a chimney, the streamers converge, swirl and disappear into a star on the map. Of course, the birds’ actual destination is much smaller than the star can illustrate. The real geographic point is a rocky bluff on private property. The entire fenced colony is approximately the size of an American football field. About 30 pairs of birds nest there, and dozens of sub-adults come and go, searching for the perfect mate. Itʻs a great spot to raise a baby, especially since it has such easy access to the prevailing wind. There is little need for a runway. The birds simply walk to the tip of the bluff, spread their wings and are summoned heavenward. Once airborne, they bank north toward Alaska.

They will cover an unbelievable expanse while they forage. We can estimate the distance from Kaua`i to the southern Aleutians to be about 2,000 miles, and the birdsʻ east-west range about the same. That means Chris’s streamers are billowing over about four million square miles. Compare and contrast: the U.S. is 3.8 million square miles. In other words, a pair of Laysan albatross may search an area the size of the entire United States to find food for their chick. Talk about your devoted, hard-working parents.

Chris said it. Even though covering such distances is unimaginable, the feat is trumped by the extraordinary fact that albatross can find their way home in such a vast empire. If a pyramid can be declared a Wonder of the World and a person can be annointed a saint, don’t you think there should be a global award for nature’s most astounding achievements? Tell you what: if I ever get a chance to serve on that nominating committee, I will vigorously lobby for albatross navigation. Ask yourself if you could find one specific acre out of millions if you had no landmarks to guide you. Even if you could read celestial guidance like a sea captain with a sextant? Oh, speaking of sextants—did I mention that the Pacific is commonly layered with clouds? Stars would be hard to see, even on the darkest night. Because of the clouds you couldn’t shout Land Ho! until you were only a few miles away from Kaua`i. I’m just saying.

Navigation and Other Forms of Wisdom

We humans are just starting to learn how we find our way across town. The 2014 Nobel Prize for Medicine was awarded to three scientists who discovered the mechanism of our inner GPS. They describe “place” and “grid” nerve cells that are responsible for giving us an idea where we are without having to consult Garmin at every turn. The first clue to their discovery came from studying activity in a rat’s brain.

If we can learn something from navigation by caged domestic rodents, imagine what we could learn from the wild long-distance travelers among us. The internationally-renowned conservationist Carl Safina, author of Eye of the Albatross, makes his case in Beyond Words: How Animals Think and What Animals Feel. “An albatross must travel 4,000 miles from her nest to find a meal and then return across thousands of miles of open ocean, to an island half-a-mile wide. Dolphins and bats virtually ‘image’ a high-definition sonic world at great speed, and in darkness. Many creatures blow us away at sight, hearing, smell, response time, diving and flying capacities, sonar abilities, migratory and homing abilities.”

There is survival wisdom everywhere you look. Consider the tallest—and one of the oldest— living beings on Earth, the mighty redwood tree. When you see a fallen giant in a grove, you scratch your head about its shallow roots. How could they possibly support hundreds of feet of height and thousands of pounds of weight? But if you study the strategy of a redwood, you discover that the roots of each tree actually create a network of roots with others, sometimes as far as 100 feet from the trunk. When a tree starts to die, a “fairy ring” of young trees often sprouts from those roots in a circle around the parent. Once you know these details, you have to ask yourself if there really is any such thing as one redwood tree. Or one anything.

Trees don’t just stick to their own kind either. They can also be intimate with fish. Check out Amy Gulick’s Salmon in the Trees: Life in Alaska’s Tongass Rain Forest.(www.salmoninthetrees.org) Salmon are born in fresh water, spend years in the ocean, then return to their stream of origin to spawn and die. “But do they really die?” Amy asks. “Or are they reincarnated as bear cubs, downy eaglets and towering trees? Bears spread the nutrients from salmon bodies in the forest, which get absorbed into tree roots. Something called “nitrogen 15″ shows up in the trees, which comes from fish. Healthy trees shade the streams and keep the water cool for fish eggs. Their roots stabilize stream banks and prevent fouling of the gravel bed. Fallen trees provide food for the insects that feed the young fish. The salmon, trees and bears live with and off each other, in a thrumming circle of life.”

Who Can Rule Out the Possibilities?

There are endless examples like these, any of which could tempt you to reconsider your bright ideas about brains. Albert Einstein, a man you might say had an above-average opportunity to be impressed with the complexity of cognition, said “Everything is energy and that’s all there is to it. Match the frequency of the reality you want and you cannot help but get that reality. It can be no other way. This is not philosophy. This is physics.”

So maybe albatross don’t find their way with their brains. Maybe they’re an energetic match for home. Maybe they want to find home with all their hearts. Maybe they just go with the flow, trusting wind and gravity to guide them. Maybe love leads them. Maybe fish find them. Maybe redwood trees rule the way. Maybe they are steered by stories. Who can rule out any of these possibilities?

Just like the birds are rooted to their place of hatch, we are anchored to certain immutable truths: when and where we were born, who our ancestors were and why they fled, what our culture admires and abhors, which wars broke out, what animals occupied our childhood, who broke our hearts, when our parents died. All these details sleep in our beds with us, often beyond awareness and more central to our lives than we could possibly remember or imagine.

Old friends of mine, a married couple, volunteered for the Peace Corps many years ago. They adopted two infants from Kolkata and brought them back to the U.S. Their son did well. Their daughter was troubled. By the time she was 14, she was regularly skipping school, using drugs, doing her best to get pregnant. To prevent her from running away, they had to sleep on the floor outside her bedroom. When she did manage to escape, she often mysteriously wound up at the city train station. Her exhausted parents finally ran out of viable therapeutic options, so they took her for a visit to India. They hoped her birth home would ground her, would give her a sense of belonging. They sought counsel from the adoption agency. When the representative opened their file, my friends discovered an astonishing fact: their daughter’s biological mother died during childbirth. In a train station.

Aren’t We All Informed by an Infinite Universal Mind?

In the winter of 1979 I was visited in a dream by my grandmother’s cousin, the cultural anthropologist Martha Warren Beckwith. I don’t recall Dr. Beckwith speaking one word. She simply presented me with her book Hawaiian Mythology. Although I hadn’t seen her since I was 10 years old, it only took that dream for Auntie Martha to profoundly influence my life. I awakened with a powerful pull to the islands. I admit I fought it. I questioned its authenticity. I tried to forget it. I blamed it on bad homemade wine. Ultimately, I only considered it because I had to put some serious distance between me and a failing relationship before it killed me. I quit my job and boarded a plane to Honolulu. Although Hawai`i was home to several generations of my ancestors, I didn’t know anyone who still lived there. I only had a few hundred dollars in my pocket. No one understood why I had to move thousands of miles away, not even me. Especially me.

All within a span of a few months that year, an albatross chick fledged from Kaua`i for the first time in what was estimated to be 1,500 years. I learned that moli meant albatross, happened upon a few of them courting, and discovered a profound kinship. I read Hawaiian Mythology and learned about the concept of ‘aumakua, guardian ancestors. So many puzzle pieces appeared in such a short time, it was as if they were asking to be assembled, as if the mystery was totally jazzed about revealing itself—-not to be solved, but to be seen.

No matter who we are or what we see, risks are constant. Our magnificent long-traveled albatross face the possibility of death everyday. Still, they keep coming home.

Maybe our job is no different. We might not have millions of square miles to cover, but we have millions of opinions separating us from our true home. Some of us have more dangerous lives than others. All of us have the possibility of finding the spiritual home where our streamers converge with all of who we are, with our connection to the cosmic brain and all the creatures made manifest. A place where we are forgiven and forgiving. A place where we are authentic. A place where we laugh. A place where our ancestors visit our dreams. Where we dive down the chimney to roost, where fish blend into our roots. Where birds show us the way. Where brave butterflies have all the milkweed they need. Where our dying days are chaperoned by fairies who whisper to us that death has always been an illusion.

If coming home is my job, and if I commit to that job, I must regularly renew my vows to it. I have to be vigilant for predators. Some of them are human, but most of them are mental. People may judge me, puff me up, scare me, anger me, inspire guilt, cause me to lose sleep, blame me, underestimate me, lie to me, waste my time. But mostly people don’t do that to me. Mostly it’s my own mind that judges me, puffs me up, scares me, angers me, inspires guilt, causes me to lose sleep, blames me, underestimates me, lies to me, wastes my time. If I want to stay above all that stuff and chatter, I have to lock my wings like a switchblade and fly steady. Many days it seems impossible.

But impossibility is a crucial aspect of any pilgrimage. If it was easy, I wouldn’t value it. It has to be unfathomable. How possible is it for a tree to give birth to baby bears? For a monarch to migrate across a county, much less a continent? For an albatross to find her fuzzy chick on a miniscule volcanic rock in the middle of the ocean? When I consider the challenges my fellow beings overcome, how can I not try to emulate their creativity and courage? As author Dani Shapiro says in her book Still Writing, “we cannot afford to walk sightless among miracles.”

If I experience the miracle of being alive on my 91st birthday, I will have received 50 more years than my mother was given. In honor of her, I promise you this: I will not wake up that day only to realize I have spent my life lost on a landscape of nonsense, littered with gossip and golden idols. When I can stay the course—providing I can actually find the course— it rocks me with gratefulness, sometimes literally. I’m there infrequently, but I’ve visited often enough to want to keep on its heels, to not let it out of my sight.

Why? Because knocked to my knees in gratitude is how I know I’ve arrived at the right address. It’s how I know my GPS works. It’s how I know I’m home.

*******************

Many mahalos to Chris Jordan, Amy Gulick and Carl Safina for their insights. Carl’s book Beyond Words: How Animals Think and What Animals Feel is scheduled for publication in 2015 and can be pre-ordered now. Chris Jordan’s film Midway will also be released in 2015.

Special thanks to Josh Adams, U.S. Geological Survey, Michelle Hester, Oikonos Ecosystem Knowledge, and Lindsay Young, Pacific Rim Conservation for the USGS map and for their data on the travels of Laysan albatross who nest on the island of Kaua`i.

*******************

Hob Osterlund

Holy Moli: Albatross & Other Awesome Ancestors